On Monday, I gave a speech at Brookings and then had a discussion with my Harvard colleague Ed Glaeser on aspects of infrastructure investment. Here are the links to the video and transcript. While for reasons described below I believe the Trump campaign proposals are wholly ill-conceived, I remain convinced that an increased and improved programme of public infrastructure investment would be very much in the American national interest. The case for public investment today rests largely on grounds of long-run policy and microeconomic efficiency given the sub-5 per cent unemployment rate.

My remarks and conversation with Ed focused on five main issues.

First, improved infrastructure has benefits that go well beyond what is picked up in standard rate of return on investment calculations. Because infrastructure is integrative, we often fail fully to understand the benefits of investment.

Nonquantitative historians are convinced that the Transcontinental railway played a crucial role in American history. They believe it permitted the integration of the west and more broadly drew our nation together. This idea was famously challenged by Nobel Prize economist Robert Fogel in his doctoral dissertation. Fogel pointed out that transport made up only a small per cent of GDP and that the railroad was only a certain per cent cheaper than canals so the contribution to economic growth had to be small. I suspect this calculation, which mirrors those usually done in evaluating infrastructure projects such as high-speed rail, misses the benefits of integrative infrastructure in spurring investment and promoting agglomeration by increasing the range over which the best companies can expand and compete. My bet is that the railway project was in fact very important for the US economy. I suspect something similar can be said on a global basis about the Suez or Panama Canal projects.

There is a broader point as well. Investments in a location can be divided between those that have “spill-out consequences” and those that have “pull-in” effects. Investments in new science, for example, have benefits that spread out widely, as do investments in educating children some of whom inevitably migrate. Investments in infrastructure on the other hand have benefits that are local to where they take place and are likely to attract other investments. For example, Dulles airport and its successive expansion has been a huge spur to the economic development of Northern Virginia. At a time of resurgent interest in the national dimension of economic success, infrastructure projects have the virtue that their benefits are very much concentrated where the investments take place.

Second, there is a particularly compelling case for maintenance investment. Ed and I agreed that there was a presumption that this should be the case since all the incentives facing political decision makers work against adequate maintenance. Deferred maintenance liabilities are largely unmeasured, unnoticed and passed on to subsequent generations of elected officials. No one can name a maintenance project. The desire to come in on budget discourages what might be called “pre-maintenance”, such as when the high-return insulation investments got stripped out at the last moment of Harvard building projects.

The examples are pretty stark. The American Society of Civil Engineers, which is admittedly an interested party, estimates that extra repairs for American automobiles each year have a cost that is the equivalent of a 75 cent a gallon gasoline tax. As I have said many times, look at La Guardia or Kennedy airport. I was struck many years ago by the young teacher who approached me in Oakland after, as secretary of the Treasury, I gave a speech about the importance of education. She said “Secretary Summers — that was a great speech. But the paint is chipping off the walls of this school, not off the walls at McDonald’s or the movie theatre. So why should the kids believe this society thinks their education is the most important thing?” I had no good answer.

As with potentially collapsing bridges, prevention is cheaper than cure and in many cases the return on “un-derferring” maintenance far exceeds government borrowing rates. Borrowing to finance maintenance should not be viewed as incurring a new cost but as shifting from the fast-compounding liability of maintenance to the slowly compounding liability of explicit debt. It should also be noted that inevitably one maintains what has been used, so maintenance investment is much less likely to turn out a white elephant than new infrastructure investment.

My guess is that the US could profitably spend an additional 0.5 per cent of GDP, or about $1.25tn over the next decade, on maintenance of its infrastructure.

Third, there are important new infrastructure investment projects that almost certainly have high rates of return. I have previously used as an example the renewal of the US air traffic control system. While vacuum tubes are no longer in use in our system, radar technology of the kind used during the second world war is pervasive, and there is essentially no role for GPS in our current architecture. The result is greater than necessary threats to safety, substantial unnecessary emission of greenhouse gases as planes circle to maintain greater than necessary distances from each other, pervasive delays during peak travel times, and inefficient usage of airport capacity. Current plans do not involve a satisfactory system being fully implemented until the mid-2030s.

The Treasury department recently released a study identifying 40 projects with a combined cost in the range of $200bn and cost-benefit ratios in the range of 2 to 10. This does not take account of technological progress. For example, autonomous vehicle technology will create new possibilities for very high speed travel lanes. And new developments in energy storage and transmission create potential for infrastructure technologies that will yield large social benefits by facilitating the adoption of renewable energy technologies like solar and wind, where intermittency is an important issue. I suspect also that pervasive fast wireless will create benefits that are currently unimaginable in the same way that the Transcontinental Railroad did.

I would be very surprised if another 0.5 per cent of GDP could not be profitably invested in new infrastructure over the next decade. A $2.5tn programme would still leave public investment at levels that are low by the standards of the post-war period in the US or other countries. Given how much less we are now spending — of the order of 3 per cent of GDP — on national defence compared to the more than 5 per cent we spent for much of the post-war period, it is not plausible to assert that we cannot afford these investments as a nation. Indeed, if over time infrastructure investments yield a return of even 6 per cent and if government can capture even 1/6 of that return in increased tax collection, they will pay for themselves at current low levels of real interest rates.

Fourth, better infrastructure investment is as important as more infrastructure investment. Quality is as important as quantity. Progressives are right to decry the inadequate level of public investment in the US. Conservative complaints about regulatory obstacles, problems in project selection, inefficient procurement and inattention to the use of pricing in assuring the efficient use of infrastructure are equally valid. The short 300-foot bridge outside my office connecting Cambridge and Boston has been under repair with substantial traffic delays for nearly five years. Julius Caesar built from scratch a bridge seven times as long spanning the Rhine in nine days! Famously, it has taken longer to repair the eastern span of the Bay Bridge in San Francisco than took to build the original. Yes, Robert Moses and his contemporaries were too heedless of the environment and the interests of local communities. But we can surely find ways of coming to far more rapid decisions with far less promiscuously distributed veto power than is the case in much of the country today.

There is too much pork barrel and too little cost-benefit analysis in infrastructure decision-making. Projects should be required to pass cost-benefit tests and proposals like a national infrastructure bank that would insulate a larger portion of decision-making from politics should be seriously considered. Ed Glaeser is right that new infrastructure investment in declining areas is often a terrible idea as shrinking populations means that these areas have if anything too much infrastructure. And Field of Dreams — “build it and they will come” approaches do not have a very good track record. Ways should be found to make the costs of procrastination on maintenance more salient and to institutionalise resistance to low-ball cost estimates from advocates of more visionary projects.

The goal of building rapidly at minimum cost should be the primary objective in infrastructure procurement. Deviations from this principle should take place only with compelling justification.

Crucially, modern technology makes possible much more pricing of infrastructure usage than was once the case. In particular, transponder technology means that usage of roads can be priced with sensitivity to exact location and time much as power is priced today. To date, congestion pricing has been very difficult politically. My hope is that in the same way that pricing in the environmental area was once decried as “purchased licences to pollute” but is today quite widely accepted, formulas can be found to introduce congestion pricing. The benefits are potentially very large. And it should be possible to find formulas to compensate losers.

To assert that current public investment decision-making is highly flawed should not be taken as a blanket endorsement of private sector reliance. While there are areas where public-private partnerships are desirable, these should be approached with great caution. The private sector often demands rates of return far greater than public sector borrowing costs, especially in the current low interest rate environment. Insisting on private participation could well substantially raise costs without addressing major problems.

The proposals of Trump advisors Peter Navarro and Wilbur Ross to rely on tax credits to augment infrastructure investment are a textbook case of the dangers of knee-jerk private sector reliance. These benefits would (i) largely go to developers and contractors for infrastructure projects like new pipelines that would happen even without new incentives and so be highly regressive; (ii) raise costs by failing to reach the tax-free pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and international investors that are the most plausible sources of incremental infrastructure finance; (iii) not encourage at all the highest return maintenance projects like fixing potholes that do not yield a pecuniary return for investors; and (iv) by offering credits at an unprecedented 82 per cent rate, invite all kinds of tax-shelter abuse.

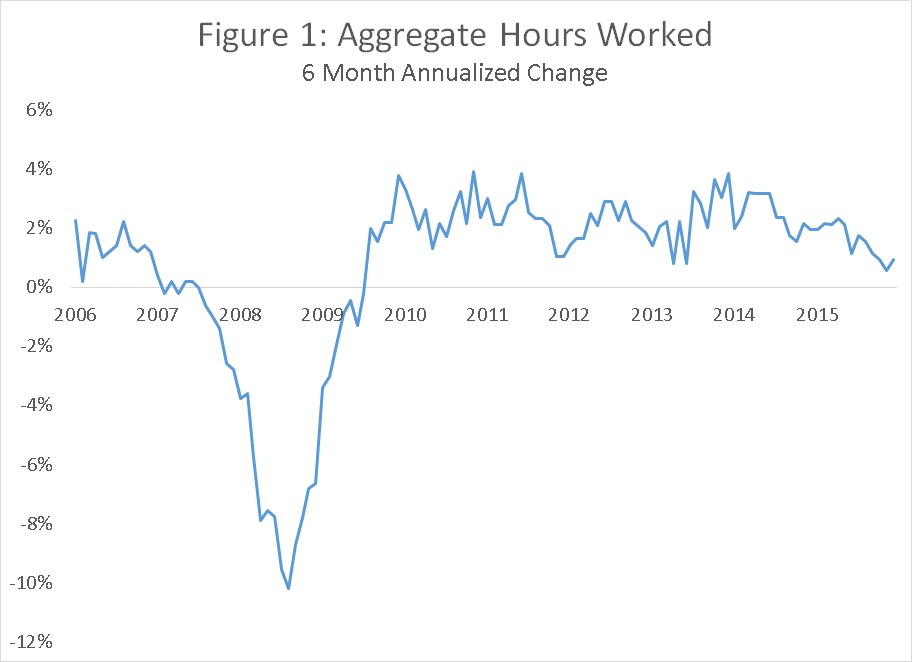

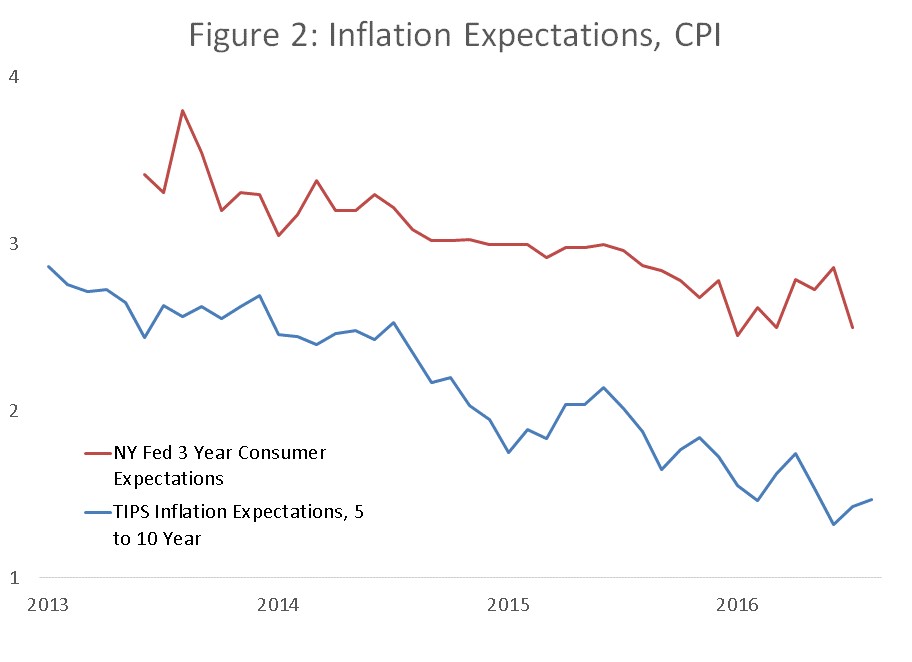

Fifth, while the case for expanded infrastructure investment does not depend on Keynesian stimulus or aggregate demand considerations, secular stagnation risks reinforce the argument for increased public investment. As the previous points illustrate, there is a compelling case (wholly apart from any ideas about aggregate demand) for increased infrastructure investment. To the extent that, as I have argued elsewhere, the industrial world is likely to be prone to a chronic excess of saving over private investment in the years ahead, this case is reinforced. Excess saving means that very low real interest costs are likely to persist, reducing the capital cost of infrastructure investment.

While the evidence is far from conclusive, my guess is that low real borrowing costs raise the risk of bubbles and financial instability. This argues for a shift in the policy mix, from monetary policy towards fiscal policy. And to the extent that, because of constraints on how low interest rates can go, recessions become more frequent and protracted in the years ahead, the case for expansionary fiscal policy is reinforced. To be clear, I do not believe that infrastructure investment can be turned on and off in response to cyclical fluctuations without big efficiency losses. And I do not believe there is a case for make-work projects that cannot be justified on microeconomic grounds. There is, however, a case for expanded public investment on a sustained basis with financing from borrowing or taxes that varies with cyclical conditions.

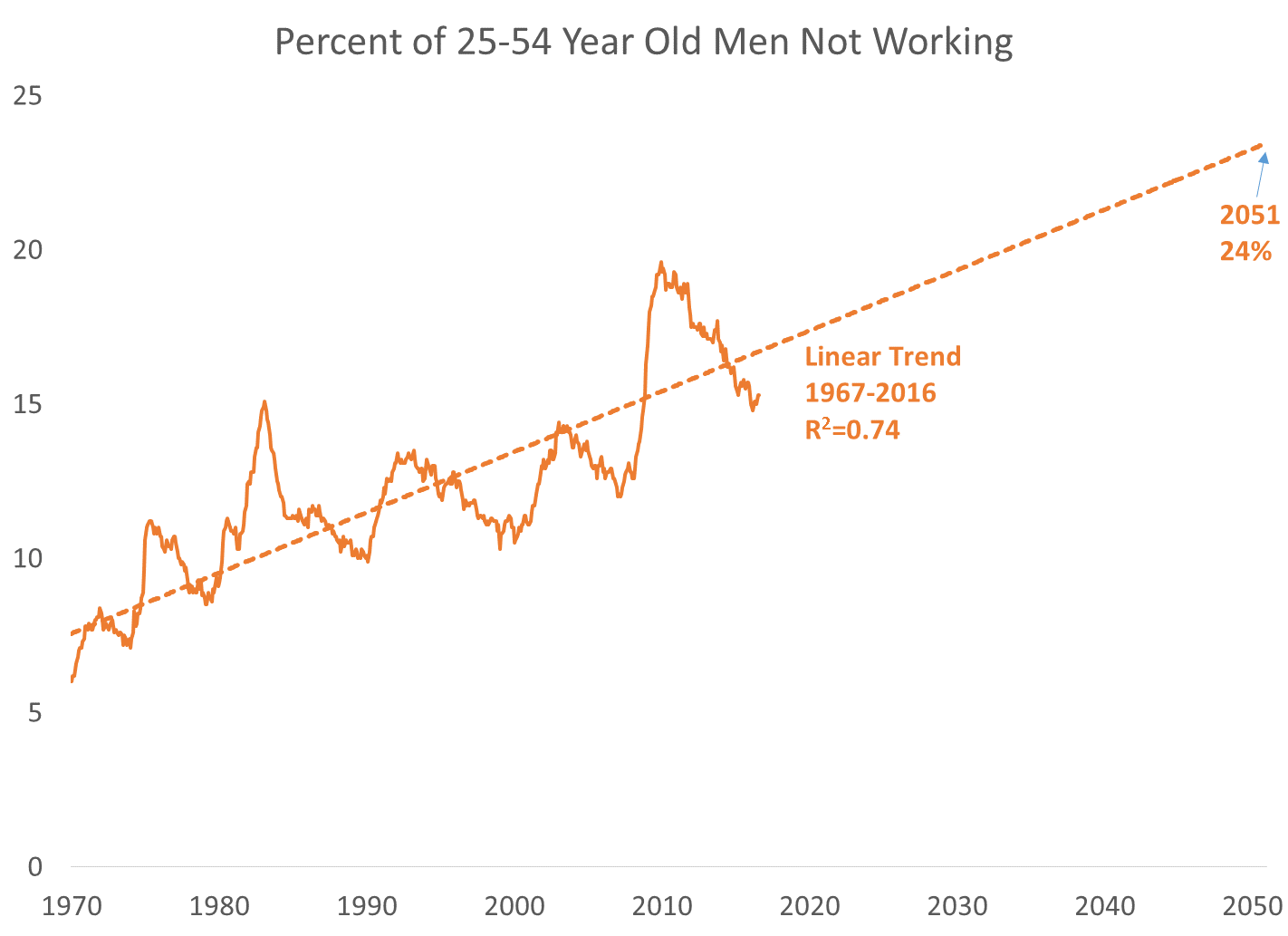

There is also the consideration that infrastructure investment is likely to disproportionately benefit groups such as middle-aged men with limited education who face a major structural employment problem. One way of thinking about this is that it means the real cost of investment is lower because those working on infrastructure would otherwise have been jobless and perhaps collecting unemployment or disability benefits. Another is to simply note that even if the economy does not face a chronic shortage of demand overall, it does face a shortage of demand for certain types of labour and policies that address this shortfall are, other things being equal, desirable.

While President-elect Trump’s plans for infrastructure stimulus are, I think, misguided and probablyharmful, I agree with the incoming administration on one thing: the case for a substantially increased programme of public infrastructure is undeniable.