05/21/2017

Several weeks ago I gave a talk based on my Brookings paper with Natasha Sarin at the Atlanta Fed’s annual research conference. Here are the video and slides. I continue to be puzzled by gap between what is widely believed and my reading of market evidence.

I began by highlighting three facts that seem to me to be in substantial tension with the widespread view that banks are far safer now than they used to be because they are far better capitalized. Mark Carney’s statement that “The capital requirements of our largest banks are now ten times higher than before the crisis. . . . This substantial capital and huge liquidity give banks the flexibility they need to continue to lend…even during challenging times” is typical.

First, there is distressingly little evidence in favor of the proposition that banks that are measured as better capitalized by their regulators are less likely to fail than other banks. Andrew Haldane suggests the absence of a relationship looking across banks before the 2008 crisis. Òscar Jordà and coauthors suggest the absence of such a relationship historically, using data for many countries. Jeremy Bulow and Paul Klemperer note that for banks whose crisis failure resulted in FDIC losses, the FDIC typically had to inject an amount in excess of 15 percent of their assets, suggesting that they in fact had substantial negative capital positions.

Second, financial logic embodied in the celebrated Modigliani Miller theorem and suggested by common sense holds that substantial reductions in leverage, if achieved, should be associated with reduced volatility, reduced sensitivity to shocks and lower risk premiums. Our paper examines a comprehensive suite of volatility measures including actual volatility, volatility implied by option pricing, beta, credit default spreads, preferred stock yields and earnings price ratios. While each indicator has associated ambiguities, it is striking that none suggest a major reduction in leverage for the largest US financial institutions, large global institutions or midsize domestic institutions.

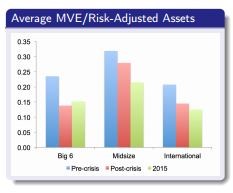

Third, the ratio of the market value of bank’s common equity to its risk weighted assets provides a market based measure of its leverage. Of course, the market value of equity overstates true capital because of limited liability: if assets rise in value there is no limit to how much shareholders can ultimately receive; but there is a zero lower bound on what shareholders receive. Still, as Haldane and others have documented, this market measure has historically proven useful in predicting bank distress. The data suggest that on a market value of equity basis, major financial institutions are no less levered than they were over the period before the crisis—even excluding the couple of years before the crisis when there was plausibly a bubble element in market pricing.

I am more confident that these observations need to be reckoned with in thinking about financial stability than I am in any particular set of explanations much less policy conclusions. Here though are some observations suggested by our findings.

First, it is essential to take a dynamic view of capital. The health of a financial institution depends critically on the profits it can expect to generate in the future. I suspect that the decline in the ratio of the market value of bank equity to assets reflects declines in expected future profits, and that this declining franchise value, other things equal, causes banks to be more levered.

The stress tests introduced by the regulatory community represent a welcome recognition of the need to take a dynamic view of capital. However I am inclined to agree with Jeremy Bulow who noted in commenting on the our paper that recent stress tests estimate that if GDP drops 6.25 percent, unemployment doubles, the stock market halves, and real estate falls by 25 to 30 percent, then capital losses would be insufficient to trigger “prompt corrective action.” Bulow wonders—and we do as well—if this is not more of a comment on the inadequacies of the stress test procedures, than on the soundness of the banks.

Second, a crucial challenge for financial regulation going forward is assuring prompt responses to deteriorating conditions that do not set off vicious cycles. Markets were sending clear signals of major problems in the financial sector well in advance of the events of the fall of 2008 but the regulatory community did not even limit bank dividend payouts, even after the experience at Bear Stearns, which had been deemed very well capitalized even as it was failing. Current experiences in Europe where some institutions have a price-to-book ratio of barely 0.35 and have not yet been forced to raise capital are not encouraging about lessons learned.

Third, regulators need to be attentive to franchise value. It goes without saying that banks should not be permitted to take excessive risks or treat customers unfairly in order to raise their franchise value. Nor would it be wise public policy to undermine competition in banking in order to raise franchise values. On the other hand, it is not just an issue of cost, but financial stability as well when regulators impose needless burdens on banks. This point was brought home to me not long ago when I heard about the legal contortions one big bank felt it had to go through when I recommended a student for a job. Would hiring the student be doing me an impermissible favor? Would not hiring the student be unfair? The debates surrounding my well-intentioned suggestion consumed hours of time on behalf of the bank’s compliance team. And I am sure such abundance of caution is commonplace at most large financial institutions. On a random Tuesday, there are hundreds of federal government employees going to work at each of our major banks, some of which have more than 10,000 people engaged in compliance activity.

Regulatory costs are an especially large issue for smaller banks since there are almost certainly economies of scale in compliance functions. There is also the crucial point that incomplete regulation which discriminates against banks in favor shadow banks may by undermine financial stability in two ways. First, shadow banks may become loci of instability. Second, weakening the franchise value of regulated institutions may make their insolvency more likely.

Fourth, bankers may be more right in their concerns about increased costs of capital and its effect on lending than economists usually suggest. Economists like Anat Admati normally rely on Modigliani-Miller considerations to argue that enhanced regulation does not raise capital costs, because it makes equity safer. If as our results suggest equity is not safer, there is every reason to suppose that bank capital costs have increased as a consequence of regulation, and that this may to some extent have reduced credit flows.

Fifth, it is high time we move beyond a sterile debate between more and less regulation. No one who is reasonable can doubt that inadequate regulation contributed to what happened in 2008 or suppose that market discipline is sufficient to contain excessive risk-taking in the financial industry. At the same time, not all regulatory expansions are desirable and in some contexts tougher regulation can be counterproductive for financial stability if it reduces profitability without offsetting benefit, if interferes with bank diversification, or if it causes regulators to become overly identified within regulated institutions. Neither the approach that holds that all increases in measured capital and other regulation are attractive, nor the one that holds that capital and other regulations should be completely scaled back is likely to prevent or contain the next financial crisis.