By Natasha Sarin and Lawrence H. Summers

March 28, 2019

First of two parts

Tax reform debates have been transformed in recent weeks by a shift in emphasis from revenue raising and progressivity to an emphasis on going after the rich for the sake of equality and justice. Bold proposals from Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, for a 70 percent marginal tax rate on top earners, and from Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts — a 2020 Democratic presidential candidate — for a wealth tax on those worth more than $50 million have attracted widespread attention.

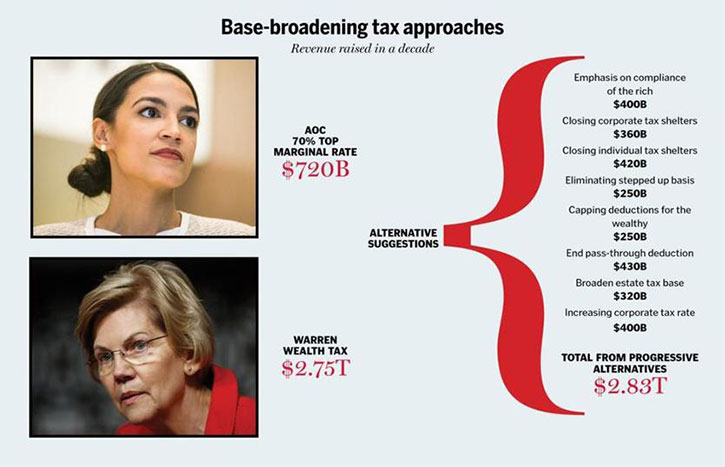

Warren’s proposal aspires to raise roughly 1 percent of GDP ($2.75 trillion in the next decade). Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal is estimated to generate around one-third of 1 percent ($720 billion in the next decade). By way of comparison, the Trump tax cuts will cost the federal government about $2 trillion over the next decade. We agree with Ocasio-Cortez and Warren that increases in tax revenue of at least this magnitude are necessary. We also agree that the way forward is by generating more revenue from the most affluent Americans. Indeed, it may well be necessary and appropriate to raise more than Warren’s targeted 1 percent of GDP from those at the top.

Where we differ from Warren and Ocasio-Cortez is in our belief that the best way to begin raising additional revenue from highest income tax payers is with a traditional tax reform approach of base broadening and loophole closing, improved compliance, and closing of shelters. We show that these measures, along with partial repeal of the Trump tax cut, can raise far more than recent proposals. These measures will increase economic efficiency, make our tax system more fair, and are perhaps more politically feasible than a wealth tax or large hikes of top rates. It may be that measures beyond base-broadening are appropriate and desirable given the magnitude of the revenue challenge we face. But base-broadening is the right place to begin.

Below we outline proposals for broadening the tax base that meet a stringent test: These are measures that would be desirable even if we did not have revenue needs. They are progressive and attack those who have received special breaks for too long. And together, the revenue-raising potential of these measures exceeds that of the 70 percent top rate or the wealth tax. We believe this is where the progressive tax policy debate should begin.

Emphasis on compliance and auditing of the rich. In 2017, the IRS had only 9,510 auditors — down from over 14,000 in 2010. The last time the IRS had fewer than 10,000 auditors was in the mid-1950s. Since 2010, the IRS budget has decreased by over 20 percent in real terms. The result is that individuals and corporations are shirking their responsibilities: The most recent estimate by the IRS suggests that taxpayers paid only around 82 percent of owed taxes, losing the IRS over $400 billion a year.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that spending an additional $20 billion on enforcement in the next decade could bring in $55 billion in additional tax revenues. This excludes the indirect deterrent effects of greater enforcement, which the Treasury Department has estimated are three times higher. Outlays at this level would still leave the IRS operating with budgets in real terms that were nearly 10 percent below peak levels, which themselves were leaving large amounts of revenue on the table.

In addition to the level of investment in enforcement, there is the question of the allocation of enforcement resources. It has been estimated that an extra hour spent auditing someone who earns more than $1 million a year generates an extra $1,000 in revenue. And yet in 2017 the IRS audited only 4.4 percent of returns with income of $1 million or higher, less than half the audit rate a decade prior. Remarkably, recipients of the earned income tax credit, who never have incomes above $50,000, are twice as likely to be audited as those who make $500,000 annually.

No one can know exactly the potential for increased enforcement to raise revenue. Suppose instead of investing an extra $20 billion over the next decade, we invested $40 billion and focused on wealthy taxpayers, perhaps taking the audit rate for million-dollar earners up to 25 percent. Considering the direct benefits and the multiplier from deterrence, it is not unreasonable to suppose that over a decade $300 billion to $400 billion could be raised.

This revenue increase — unlike a revenue increase from new taxes or higher rates — will have favorable incentive effects. It will encourage people to participate in the above-ground economy. And what could be more of a step toward fairness than collecting from wealthy scofflaws?

Closing corporate tax shelters. All too often, corporations are able to make use of tax havens, differences in accounting treatment across jurisdictions, and other devices to reduce tax liabilities. Economist Kimberly Clausing estimates that profit-shifting to tax havens costs the United States more than $100 billion a year. Although the Trump tax plan sought to reduce the incentives for profit-shifting, various exemptions and design flaws mean that the new system does little to deter shifting revenues to tax havens. Fairly incremental changes will have a large impact: For example, a per-country corporate minimum tax rather than a global minimum tax will increase tax revenues by nearly $170 billion in a decade.

But there is much more to be done. A robust attack on tax shelters — that included, for example, tariffs or penalties on tax havens as well as stricter penalties for lawyers and accountants who sign off on dubious shelters — could raise twice the revenue attainable from a per-country minimum tax, or about 30 billion annually. It would also encourage the location of economic activity in the United States and discourage the vast intellectual ingenuity that currently goes into tax avoidance.

Closing individual tax shelters. Like the corporations they own, wealthy individuals make use of myriad loopholes in the tax code to shelter their personal income from taxation. Most high-income taxpayers pay a 3.8 percent tax that pays into entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare. However, some avoid these payroll taxes by setting up pass-through businesses and re-characterizing large shares of their income as profits from business ownership, rather than wage income. The Obama administration’s proposals to close payroll tax loopholes were estimated to generate $300 billion over a decade.

Another egregious loophole is 1031 exchanges, which allow real estate investors to sell property, take a profit, and defer paying taxes on those profits so long as they reinvest them in similar investments. There is no limit on the number of these exchanges that investors can make. Consequently, the wealthy use 1031 exchanges to build up long-term tax-deferred wealth that can eventually be passed down to their heirs without taxes ever being paid. Outright repeal of 1031 exchanges were estimated in 2014 to raise around $40 billion in a decade and would raise almost $50 billion today.

Another tool used to shelter individual income from taxation is carried interest. Income that flows to partners of investment funds is often treated as capital gains and taxed at lower rates than ordinary income. This creates a tax-planning opportunity for investors to convert ordinary income into long-term capital gains that receive much more generous tax treatment. President Trump repeatedly vowed that his signature tax cuts would eliminate the carried-interest loophole, saying it was unfair that the ultra-wealthy were “getting away with murder.” However, in the face of significant lobbying pressure, the administration abandoned these plans. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that taxing carried profits as ordinary income would generate over $20 billion in a decade.

Other ways in which individuals can shelter income include misvaluing interests such as shares in investment partnerships when putting them in retirement accounts as well as schemes involving nonrecourse lending.

Closing tax shelters would level the playing field in favor of investments by companies that create jobs and to the detriment of various kinds of financial operators. This would raise employment and incomes as well as contributing to fairness.

Eliminating “stepped-up basis.” Wealth tax advocates rightly point to an important gap in our current system. An entrepreneur starts a company that turns out to be highly successful. She pays herself only a small salary, and shares in the company do not pay dividends, so the company can invest in growth. The entrepreneur becomes very wealthy without ever having paid appreciable tax, as the income that made the wealth possible represents unrealized capital gains.

Unrealized capital gains explain how Warren Buffett can pay only a few million dollars in taxes in a year when his wealth goes up by billions. Astoundingly, no capital gains tax is ever collected on appreciation of capital assets if they are passed on to heirs. Specifically: When an investor buys a stock, the cost of that purchase is the tax basis. If the stock rises in value and is then sold, the investor pays taxes on the gains. If an investor dies and leaves stock to her heir, that cost basis is “stepped up” to its price at the time the stock is inherited. The gain in value during the investor’s life is never taxed.

Implementing the Obama administration’s proposals for constructive realization of capital gains at death would raise $250 billion in the next decade. This is a progressive change that would impact only the very wealthy: Ninety-nine percent of the revenue from ending stepped-up basis will be collected from the top 1 percent of filers.

Eliminating stepped-up basis will also make the economy function better and so would be desirable even if it did not raise revenue. The fact that capital gains passed on to children entirely escape taxation provides aging small-business owners or real estate owners a strong incentive not to sell them to those who could operate them better while they are alive. It also makes it much more expensive to realize capital gains and use the proceeds to make new investments than it would be if the capital gains tax was inescapable.

Capping tax deductions for the wealthy. Today, a homeowner in the top tax bracket (post-Trump tax cuts, 37 percent) who makes a $1,000 mortgage payment saves $370 on her tax bill. Under an Obama administration proposal to limit the value of itemized deductions to 28 percent for all earners, that same write-off would save this wealthy taxpayer just $280. Importantly, such a cap would raise tax burdens only for the rich: Those with marginal rates under the cap would still be able to claim the full value of their itemized deductions. The plan to cap top-earners’ itemized deductions was estimated to raise nearly $650 billion in a decade. Recognizing that the Trump tax plan scaled back the mortgage interest deduction and state and local tax deductions, we estimate that additional limits on top-earner deductions could generate around $250 billion in a decade.

As with the elimination of stepped-up basis, the distributional case for capping tax deductions is strong. The mortgage interest deduction provides a tax advantage to homeowners; promoting homeownership is a worthy goal. But there is little rationale for subsidizing home ownership at higher rates for richer rather than poorer taxpayers.

End the 20 percent pass-through deduction. Perhaps the most notorious of the Trump tax changes, the pass-through deduction provides a 20 percent deduction for certain qualified business income. This exacerbated the tax code’s existing bias in favor of noncorporate business income and so reduces economic efficiency. And the complex maze of eligibility is arbitrary, foolish, and a drain on government resources: The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that this provision will reduce federal revenues by $430 billion in the next decade. Eliminating the pass-through deduction will reduce incentives for tax gaming and raise revenue primarily from taxpayers making more than $1 million annually.

Broaden the estate tax base. Prior to the Trump tax reform, only 5,000 Americans were liable for estate taxes. The recent changes more than halved that small share by doubling the estate tax exemption to $22.4 million per couple. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that this change costs around $85 billion, with the benefits accruing entirely to 3,200 of the wealthiest American households. Repealing the Trump administration’s changes and applying estate taxes even more broadly — for example, as the Obama administration proposed, by lowering the threshold to $7 million for couples — would raise around $320 billion in a decade. The estate tax would still only impact 0.3 percent of decedents.

In addition to the question of the appropriate floor on estates, there is also ample room to attack the many loopholes that enable wealthy families to largely avoid paying taxes when transferring wealth to their progeny during their lifetimes. This happens through a mix of trust arrangements, intra-family loans, and dubious valuation practices to evade gift-tax liability. Strengthening the taxation of estates would raise revenue and be efficient, diverting resources from tax planning and increasing work incentives for the children of the wealthy. We are enthusiastic about proposals, notably by Lily Batchelder, that call for the conversion of the estate tax into an inheritance tax, to appropriately tax inherited privilege and discourage large concentrations of wealth.

Increasing the corporate tax rate to 25 percent. When corporations began lobbying efforts on corporate tax reform, their stated objective was a 25 percent corporate rate. Business leaders produced estimates showing how this 25 percent rate would have prevented foreign purchases of thousands of companies and shifted billions in corporate taxable income to the United States. The Trump tax cuts delivered more than the business community asked, slashing the corporate rate to 21 percent. The CBO estimates that a 1 percentage point increase in the corporate tax rate will generate $100 billion in the next decade. Based on this estimate, a 4 percentage point increase to 25 percent will generate an additional $400 billion in revenue.

Raising the corporate tax rate would not increase the tax burden on most new investment, because it would raise in equal measure the value of the depreciation deductions that corporations could take when they undertook investments. The principle losers from an increase in the rate would be those earning economic rents in the form of monopoly profits and those who had received enormous windfalls from the Trump tax cut.

Closing tax shelters used by the wealthy alone raises more revenue than Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal. And together, the reforms we propose raise far more than a 70 percent top tax rate, and more too than Warren claims her wealth tax will generate. These base-broadening, efficiency-enhancing reforms are the best way to start raising revenue as progressively and efficiently as possible. To be sure, it may well be that wealth taxation or large increases in top rates are necessary to adequately fund government activities. But we advocate these approaches only after the revenue-raising potential of base-broadening is exhausted.

Tomorrow: The challenges in the rate hike and wealth tax proposals.