In the May/June 2016 issue of Foreign Affairs, Summers and Mahbubani explore the case for global optimism. The essay states, “Historians looking back on this age from the vantage point of later generations, however, are likely to be puzzled by the widespread contemporary feelings of gloom and doom. By most objective measures of human well-being, the past three decades have been the best in history. More and more people in more and more places are enjoying better lives than ever before.” (more…)

Search Results for: STAGnation

Reflections the Recession, Higher-ed & the Economy

April 19th, 2016

Harvard Magazine profiled a conversation with Summers on a variety of issues, including the recession, higher-ed and the economic environment. Summers said, “Harvard will have to choose between its commitment to preeminence and its commitment to doing things in traditional ways.” (more…)

Corporate profits are near record highs. Here’s why that’s a problem.

March 30th, 2016

As the cover story in this week’s Economist highlights, the rate of profitability in the United States is at a near-record high level, as is the share of corporate revenue going to capital. The stock market is valued very high by historical standards, as measured by Tobin’s q ratio of the market value of the nonfinancial corporations to the value of their tangible capital. And the ratio of the market value of equities in the corporate sector to its GDP is also unusually high.

All of this might be taken as evidence that this is a time when the return on new capital investment is unusually high. The rate of profit under standard assumptions reflects the marginal productivity of capital. A high market value of corporations implies that “old capital” is highly valued and suggests a high payoff to investment in new capital.

This is an apparent problem for the secular stagnation hypothesis I have been advocating for some time, the idea that the U.S. economy is stuck in a period of lethargic economic growth. Secular stagnation has as a central element a decline in the propensity to invest leading to chronic shortfalls of aggregate demand and difficulties in attaining real interest rates consistent with full employment.

Yet matters are more complex. For some years now, real interest rates on safe financial instruments have been low and, for the most part, declining. And business investment is either in line with cyclical conditions or a little weaker than would be predicted by cyclical conditions. This is anomalous, as in the most straightforward economic models the real interest rate is the risk adjusted rate of return on capital. And an unusually high rate of investment would be expected to go along with a high rate of return on existing capital.

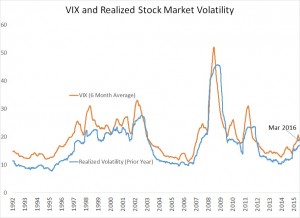

How can this anomaly be resolved? There are a number of logical possibilities. First, the riskiness associated with capital investment might have gone up and so higher rates of return could be simply compensating for higher risk rather than implying attractive investments. There are two major problems with this story. One is that available proxies for risk are not especially high in recent years. The chart below depicts realized stock market volatility and the VIX measure of expected volatility as implied by options. Another problem is that if capital returns have become far more uncertain, then the stocks should have become less attractive in recent years rather than more. In the last 7 years, the stock market has risen to 250 percent of its spring 2009 levels.

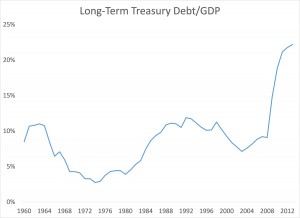

A second explanation could be that a heightened demand for liquidity and a shortage of Treasury instruments, perhaps created by quantitative easing programs, has driven down bond yields, widening the spread between the rate of profit and these yields. This story does not provide a natural explanation for the relatively weak behavior of business investment. Further as Sam Hanson, Robin Greenwood, Joshua Rudolph and I pointed out in earlier work, the market is today being asked to absorb an abnormally high rather than an abnormally low level of long term Federal debt.

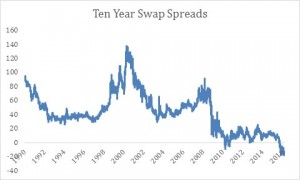

On top of that, if Treasuries were in short supply, one would expect that they would have their yield bid down relative to market synthesized safe instruments. Yet the so-called swap spread is actually negative and Treasury yields (vs swaps) are unusually high relative to history.

Third, it could be that higher profits do not reflect increased productivity of capital but instead reflect an increase in monopoly power. If monopoly power increased one would expect to see higher profits, lower investment as firms restricted output, and lower interest rates as the demand for capital was reduced. This is exactly what we have seen in recent years!

Is the increased monopoly power theory plausible? The Economist makes the best case I have seen for it noting that (i) many industries have become more concentrated (ii) we are coming off a major merger wave (iii) there is some evidence of greater profit persistence among major companies (iv) new business formation has declined (v) overlapping ownership of companies that compete has become more common with the rise of institutional investors, (vi) leading technology companies like Google and Apple may be benefiting from increasing returns to scale and network effects.

The combination of the fact that only the monopoly power story can convincingly account for the divergence between the profit rate and the behavior of real interest rates and investment, along with the suggestive evidence of increases in monopoly power makes me think that the issue of growing market power deserves increased attention from economists and especially from macroeconomists.

A world stumped by stubbornly low inflation

March 7th, 2016

Here is a thought experiment that illuminates the challenges currently facing macroeconomic policymakers in the US and the rest of the industrial world.

Imagine that in a brief period inflation expectations around the industrial world, as inferred from both the markets for indexed bonds or inflation swaps, rose by nearly 50 basis points to a level well above the 2 per cent target with larger increases foreseen at longer horizons.

Imagine that at the same time survey measures of inflation expectations, such as those calculated by the University of Michigan and New York Federal Reserve in the US, were rising sharply.

Imagine also that commodity prices were soaring and that the dollar experienced a decline seen once every 15 years.

Imagine that the market estimate of future monetary policy in the US was far tighter than the Federal Reserve’s own policy projections.

Imagine that measures of gross domestic product growth were accelerating with increasing signs of a worldwide boom.

Imagine too that no serious efforts were under way to reduce deficits.

Finally, suppose that officials were comfortable with current policy settings based on the argument that Phillips curve models predicted that inflation would revert over time to target due to the supposed relationship between unemployment and price increases.

I think it is fair to assert that in this hypothetical circumstance there would be pervasive concern that policy was behind the curve. There would be fears that much was at risk as inflation expectations were becoming unanchored and that a substantial set of policy adjustments were appropriate.

The key point is that allowing not just a temporary increase in inflation but a shift to abovetarget inflation expectations could be very costly.

At present we are living in a world that is the mirror image of the hypothetical one just described. Market measures of inflation expectations have been collapsing and on the Fed’s preferred inflation measure are now in the range of 1-1.25 per cent over the next decade.

Inflation expectations are even lower in Europe and Japan. Survey measures have shown sharp declines in recent months. Commodity prices are at multi-decade lows and the dollar has only risen as rapidly as in the past 18 months twice during the past 40 years when it has fluctuated widely.

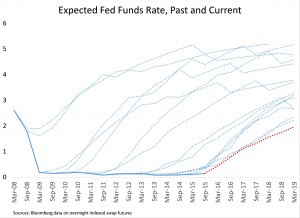

The Fed’s most recent forecasts call for interest rates to rise almost 2 per cent in the next two years, while the market foresees an increase of only about 0.5 per cent.

Consensus forecasts are for US growth of only about 1.5 per cent for the six months from last October to March. And the Fed is forecasting a return to its 2 per cent inflation target on the basis of models that are not convincing to most outside observers.

Despite the apparent symmetry, the current mood is nothing like the one posited in my hypothetical example.

While there is certainly substantial anxiety about the macroeconomic environment, as judged from the meeting of the Group of 20 big economies in Shanghai last week, there is no evidence that policymakers are acting strongly to restore their credibility as inflation expectations fall below target.

In a world that is one major adverse shock away from a global recession, little if anything directed at spurring demand was agreed. Central bankers communicated a sense that there was relatively little left that they can do to strengthen growth or even to raise inflation. This message was reinforced by the highly negative market reaction to Japan’s move to negative interest rates. No significant announcements regarding non-monetary measures to stimulate growth or a return to target inflation were forthcoming, either.

Perhaps this should not be surprising. In the 1970s it took years for policymakers to recognise how far behind the curve they were on inflation and to make strong policy adjustments.

Policymakers continued to worry about a supposed lack of demand long after it was an important problem. The first attempts to contain inflation were too timid to be effective and success was achieved only with highly determined policy. A crucial step was the abandonment of the idea that the problem was structural in nature rather than driven by macroeconomic policy.

Today’s risks of embedded low inflation tilting towards deflation and of secular stagnation in output growth are at least as serious as the inflation problem of the 1970s. They too will require shifts in policy paradigms if they are to be resolved.

In all likelihood the important elements will be a combination of fiscal expansion drawing on the opportunity created by super low rates and, in extremis, further experimentation with unconventional monetary policies.

Equitable Growth in Conversation

February 12th, 2016

Summers talks with Heather Boushey, of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, about how inequality affects economic growth and stability. The discussion explores secular stagnation—what it is, what problems it creates, and the issues for policymaking—as well as how inequality plays a role in the phenomenon.

(more…)

Economy Can’t Withstand 4 Fed Hikes In 2016

January 21st, 2016

Policy makers need to heed the message from global commodity and stock markets that “risks are substantially tilted to the downside,” said Summers on Bloomberg GO on January 13, 2016. (more…)

Thoughts on Delong and Krugman blogs

January 1st, 2016

Brad Delong and Paul Krugman accept my criticisms of Fed thought regarding their monetary policy strategy but disagree with my assertion that it reflects an excessive attachment to existing models and modes of thought.

Their argument is that standard IS-LM leads to the conclusion you should not raise rates in the present environment so no move away from orthodoxy is necessary to reach this conclusion. I think the issue is more on the supply side than the demand side. If I believed strongly in the vertical long run Phillips curve with a NAIRU around five percent and in inflation expectations responsiveness to a heated up labor market, I would see a reasonable case for the monetary tightening that has taken place.

Since I am not sure of anything about the Phillips curve and inflation is well below target I come down against tightening. The disagreement does it seems to me come down to the Fed’s attachment to the standard Phillips curve mode of thought. My disagreement is reinforced by other judgmental aspects that are outside of the standard model used within the Fed. These include hysteresis effects, the possibility of secular stagnation, and the asymmetric consequences of policy errors.

I am sure Paul and Brad are right that a desire to be “sound” also influences policy. I am not nearly as hostile to this as Paul. I think maintaining confidence is an important part of the art of policy. A good example of where market thought is I think right and simple model based thought is I think dangerously wrong is Paul’s own Mundell-Fleming lecture on confidence crises in countries that have their own currencies. Paul asserts that a damaging confidence crisis in a liquidity trap country without large foreign debts is impossible because if one developed the currency would depreciate generating an export surge.

Paul is certainly correct in his model but I doubt that he is in fact. Once account is taken of the impact of a currency collapse on consumers’ real incomes, on their expectations, and especially on the risk premium associated with domestic asset values, it is easy to understand how monetary and fiscal policymakers who lose confidence and trust see their real economies deteriorate as Olivier Blanchard and his colleagues have recently demonstrated. Paul may be right that we have few examples of crises of this kind but if so this is perhaps because central banks do not in general follow his precepts.

I do not think this is a pressing issue for the US right now. But the idea that policymakers should in general follow the model and not worry about considerations of market confidence seems to me as misguided as the view that they should be governed by market confidence to the exclusion of models.

Rate Delay Less Risky Than Premature Hike

December 15th, 2015

In an interview with Tom Keene of Bloomberg Surveillance from the Arab Strategy Forum in Dubai, Summers voiced skepticism surrounding an expected Federal Reserve rate hike and the impact of lower commodities prices and devaluing currencies. Summers also discussed his thoughts on secular stagnation. Watch the full interview here. (more…)

Breaking new ground on neutral rates

December 14th, 2015

Lukasz Rachel and Thomas Smith have a terrific new paper on world neutral real rates. The fact that it supports a variety of arguments that I have been making on secular stagnation for the last two years may contribute to my enthusiasm but the paper breaks new ground in a number of respects.

First, Rachel and Smith document compellingly the near universality of sharply declining real rates and also the length and breadth of the decline. They show the phenomenon is a very broad based 450 basis point trend decline in real rates occurring over 25 years. Framing the problem this way is significant because it shows the inadequacy of shorter-term explanations of low neutral real rates such as those of Ken Rogoff that focus on the financial crisis and its aftermath. It also suggests the need to look beyond monocausal.

Second, Rachel and Smith do not find that slowing growth is the main explanation for declining real rates. Rather they attempt to quantify most of the factors that I and others have enumerated in accounting for declining real rates. They note that since the global saving and investment rate has not changed much even as real rates have fallen sharply there must have been major changes in both the supply of saving and demand for investment. They present thoughtful calculations assigning roles to rising inequality and growing reserve accumulation on the saving side and lower priced capital goods and slower labor force growth on the investment side. They also note the importance of rising risk premia associated in part with an increase financial frictions. Rachel and Smith’s work is not the last word but it is the first important word on decomposing the causal factors behind declining real rates.

Third, Rachel and Smith use their analysis of the determinants of neutral real rates to predict their future evolution. Here they reach the important conclusion that there is little basis for assuming a significant increase in neutral real rates going forward. This conclusion differs sharply from the “headwinds” orthodoxy prevailing in the official community. As the figure below illustrates, in the United States at least the Fed and the forecasting community has been consistently far behind the curve in recognizing that the neutral real rates has fallen. If, as I suspect, Rachel and Smith are right there will be much less scope to raise rates in the industrial world over the next few years than the world’s central banks suppose.

Fourth, Rachel and Smith recognize that their findings are highly problematic for the existing central banking order. They imply that the zero lower bound is likely to be a major issue at least intermittently going forward. After all, we will have future recessions and when we do, there will be a need to drop rates by 300 basis points or more. Perhaps QE or negative rates or forward guidance will be availing. I am skeptical that they will be efficacious if a recession comes in an economy without a heavily disrupted financial system in need of repair.

Rachel and Smith also share my concern that a world of chronic very low real rates is going to be a world of high volatility, imprudent risk taking, excessive leverage and frequent financial accident. We may be about to get a taste of this in emerging markets and US high yield markets. It is fashionable to invoke the brave new world of macro-prudential policy in response. To borrow from Wilde, I fear that enthusiasm for macroprudential policy is the triumph of hope over experience. In the last wave of enthusiasm for such policies the poster-child was Spain’s countercyclical capital requirements. They did not work out so well. As best I can tell US macroprudential policy as currently practiced has meaningfully impaired liquidity in some key markets and damaged the credit availability for small and medium sized businesses while not touching excessive flows to emerging markets and high yield corporate issuance. To work, macroprudential policy has to reduce financial vulnerabilities without to an equal extent reducing credit flows that stimulate demand. This is logically possible. I doubt that actual regulators who after all were proclaiming the health of the banking system in mid 2008 are capable of pulling it off consistently given the pressures they face.

There are no certainties here. It is possible that neutral real rates will rise over the next several years. But there is a high enough chance that they will not to make contingency planning an urgent priority. That has been and is the main thrust of the secular stagnation argument.

Central bankers do not have as many tools as they think

December 6th, 2015

This $13 trillion question is more important than ever

November 9th, 2015

The Hutchins Center for Fiscal and Monetary Policy at Brookings is having a conference launching an important new volume on federal debt management policy. Just as in the Great War in became clear that war is too important to be left to generals, so too in the Great Recession it became clear that (government) debt management is too important to be left to the parochial world debt managers. The composition of federal debt is itself often a useful tool for economic policy, particularly in the current low rate environment in which the Federal Reserve will frequently be unable to cut rates as much as it would like and will instead be reliant on “unconventional” policies intended to effect the price of government debt.

Edited by David Wessel the volume contains two chapters that I coauthored with Robin Greenwood, Sam Hanson, and Josh Rudolph as well as some separate comments of mine. There is also a provocative paper by John Cochrane and a variety of perceptive commentaries by people with experience in debt management policy.

I think the volume makes a case for quite radical revisions in thinking about debt management policy. Here are my 10 main takeaways starting where I am most confident.

- Debt management is too important to leave to Federal debt managers and certainly to leave to the dealer community. This is because, especially when interest rates are near zero, it implicates directly monetary and fiscal policy and economic performance in the short run, and questions of financial stability in the medium run.

- Whatever one’s view about desirable policy, it is fairly crazy for the Federal Reserve and Treasury, which are supposed to serve the national interest, to pursue diametrically opposed debt management policies. This is what has happened in recent years with the Federal Reserve seeking to shorten outstanding maturities and the Treasury seeking to term them out.

- Standard discussions of QE — which focus on the size of Fed purchases of long term bonds and ignore the scale of Treasury sale of these instruments — are intellectually incoherent. It is the total impact of government activities on the stock of debt that the public must hold that should impact financial markets.

- The preceding point is highly significant for the United States. Despite QE the quantity of long term debt that the markets had to absorb in recent years was well above, rather than below, normal. This suggests that if QE was important in reducing rates or raising asset values it was because of signaling effects regarding future monetary policies not because of the direct effect of Fed purchases.

- The standard mantra that Federal debt management policies should seek to minimize government borrowing costs is some combination of wrong and incomplete. It is wrong because it is risk adjusted expected costs that should be considered. It is incomplete because it is hard to see why the effects of debt policies on levels of demand and on financial stability should be ignored.

- The tax smoothing aspect, which is central to academic theories of debt policy, is of trivial significance. Even far larger levels of tax variability than we observe, or than could be offset by altered debt management policies, have only trivial impacts on levels of income. It is much more important to understand debt management policy impacts on financial stability than on tax variability.

- The idea of rollover risk that is ever present in policy discussions is very confused. If there is the possibility that a period will come when the government’s borrowing rate will be very high this obviously needs to be considered in setting policy. But the problem is not one of rollover. To see this, think about long term floating rate debt. Such debt does not offer insulation in the hypothetical circumstance where rollover would be difficult, because in such a situation floating rate debt yield will rise precipitously.

- Yield curves typically slope upward. The “carry trade” of borrowing short and lending long is a hedge fund staple. Rather than providing this opportunity Treasury should reverse the trend towards terming out the debt. Issuing shorter term debt would also help meet private demands for liquid short term instruments without encouraging risky structures like banks engaged in maturity transformation.

- Institutional mechanisms should be found to insure that in the future the Fed and Treasury are not pushing debt durations in opposite directions. The Treasury terming out the debt which the Fed then buys in an effort to quantitatively ease serves only to enrich the dealer community.

- Now that we are in a “secular stagnation” world of low interest rates, it is likely that debt management tools will be more important to stabilization policies in the future than in the past.

Advanced economies are so sick we need a new way to think about them

November 3rd, 2015

An ebook containing the papers and presentations from the European Central Bank’s central banking forum conference in Sintra Portugal is now available. Mario Draghi and his colleagues are to be greatly commended for running a forum that is so open to profound challenges to central banking orthodoxy.

The volume contains a paper by Olivier Blanchard, Eugenio Cerutti and me on hysteresis and separately some of my reflections asserting the need for a new Keynesian economics that is more Keynesian and less new. Here I summarize these two papers.

Hysteresis Effects

Blanchard Cerutti and I look at a sample of over 100 recessions from industrial countries over the last 50 years and examine their impact on long run output levels in an effort to understand what Blanchard and I had earlier called hysteresis effects. We find that in the vast majority of cases output never returns to previous trends. Indeed there appear to be more cases where recessions reduce the subsequent growth of output than where output returns to trend. In other words “super hysteresis” to use Larry Ball’s term is more frequent than “no hysteresis.”

This finding does not in and of itself establish the importance of hysteresis effects. It might be that when underlying growth rates fall recessions follow but that recessions have no causal impact going forward. In order to address this issue we look at the impact of recessions with different precursors. We find that even recessions that are associated with disinflationary monetary policies or the drying up of credit have substantial long run output effects suggesting the presence of hysteresis effects.

In subsequent work Antonio Fatas and I have looked at the impact of fiscal policy surprises on long run output and long run output forecasts using a methodology pioneered by Blanchard and Leigh. Since fiscal policy effects operate primarily through aggregate demand, this provides a way to avoid the causation question. We find that fiscal policy changes have large continuing effects on levels of output suggesting the importance of hysteresis.

I was struck that in a vote taken at the conference close to 90 percent of the participants indicated that they believe there are significant hysteresis effects. While there is much more work to be done, I believe that as of right now the right presumption is in favor of hysteresis effects despite their exclusion from the standard models used in almost all central banks.

Towards a New Macroeconomics

My separate comments in the volume develop an idea I have pushed with little success for a long time. Standard new Keynesian macroeconomics essentially abstracts away from most of what is important in macroeconomics. To an even greater extent this is true of the DSGE (dynamic stochastic general equilibrium) models that are the workhorse of central bank staffs and much practically oriented academic work.

Why? New Keynesian models imply that stabilization policies cannot affect the average level of output over time and that the only effect policy can have is on the amplitude of economic fluctuations not on the level of output. This assumption is problematic at a number of levels.

First, if stabilization policies cannot effect average levels of employment and output over time they are not nearly as important as if they can. Beginning the study of stabilization with this assumption takes away much of the motivation for doing macroeconomics.

Second, the assumption is close to absurd. It is surely reasonable to assume that better policy could have avoided the Depression or the huge output losses associated with the financial crisis without having shaved off some previous or subsequent peak.

Third, contrary to the now common view that macroeconomics is best understood by studying the stochastic properties of stationary time series, the most important macroeconomic events are in some sense one off. Think of the Depression or the Great Recession or the high inflation of the 1970s.

The problem has always been that it is difficult to beat something with nothing. This may be changing as topics like hysteresis, secular stagnation, and multiple equilibrium are getting more and more attention. As well they should. US output is now about 10 percent below a trend estimated through 2007. If one attributes even half of this figure to the effects of recession and assumes no catch up on this component until 2030 the cost of the financial crisis in the USA is about 1 year’s GDP. And matters are worse in the rest of the industrial world.

As macroeconomics was transformed in response to the Depression of the 1930s and the inflation of the 1970s, another 40 years later it should again be transformed in response to stagnation in the industrial world. Maybe we can call it the Keynesian New Economics.

The case for expansion

October 7th, 2015

Policymakers must abandon structural reform rhetoric and embrace fiscal stimulus

October 7, 2015

As the world’s financial policymakers convene for their annual meeting on Friday in Peru, the dangers facing the global economy are more severe than at any time since the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in 2008.

The problem of secular stagnation – the inability of the industrial world to grow at satisfactory rates even with very loose monetary policies – is growing worse in the wake of problems in most big emerging markets, starting with China.

This raises the spectre of a vicious global cycle in which slow growth in industrial countries hurts emerging markets which export capital, thereby slowing western growth further. Industrialised economies that are barely running above stall speed can ill-afford a negative global shock.

Policymakers badly underestimate the risks of both a return to recession in the west and of a global growth recession. If a recession were to occur, monetary policymakers lack the tools to respond.

There is essentially no room left for easing in the industrial world. Interest rates are expected to remain very low almost permanently in Japan and Europe and to rise only very slowly in the US.

Today’s challenges call for a clear global commitment to the acceleration of growth as the main goal of macroeconomic policy. Action cannot be confined to monetary policy.

There is an old proverb: “You do not want to know the things you can get used to.” It is all too applicable to the global economy in recent years. While the talk has been of recovery from the crisis, forecasts of future gross domestic product have been revised sharply downwards almost everywhere.

Relative to its 2012 forecasts, the International Monetary Fund has revised its estimate for the level of US GDP for 2020 downwards by 6 per cent, Europe by 3 per cent, China by 14 per cent, emerging markets by 10 per cent and 6 per cent for the world as a whole.

These dismal results assume no recessions in the industrial world and the absence of systemic crises in the developing world. Neither can be taken for granted.

We are in a new macroeconomic epoch where the risk of deflation is higher than that of inflation and we cannot rely on the self-restoring features of market economies. The effects of hysteresis – where recessions are not just costly but stunt the growth of future output – appear far stronger than anyone imagined a few years ago.

Western bond markets are sending a strong signal that there is too little, rather than too much, government debt. As always, when things go badly there is a great debate between those who believe in staying the course and those who urge a serious correction. I am convinced of the urgent need for substantial changes in the world’s economic strategy.

History tells us that markets are inefficient and often wrong in their judgments about economic fundamentals. It also teaches us that policymakers who ignore adverse market signals because they are inconsistent with their preconceptions risk serious error.

This is one of the most important lessons of the onset of the financial crisis in 2008. Had policymakers heeded the pricing signal on the US housing market from mortgage securities, or on the health of the financial system from bank stock prices, they would have reacted far more quickly to the gathering storm. There is also a lesson from Europe. Policymakers who dismissed market signals that Greek debt would not be repaid in full delayed necessary adjustments – at great cost.

Lessons from the bond market

It is instructive to consider what government bond markets in the industrialised world are implying today. These are the most liquid financial markets in the world and reflect the judgments of a very large group of highly informed traders. Two conclusions stand out.

First, the risks tilt heavily towards inflation rates that are below official targets. Nowhere in the industrial world is there an expectation that central banks will hit their 2 per cent targets in the foreseeable future. Inflation expectations are highest in the US – and even there it expects inflation of barely 1.5 per cent for the five-year period starting in 2020.

This is despite the fact that the market indicates that monetary policy will remain looser than the Federal Reserve expects: the Fed funds futures market predicts a rate around 1 per cent at the end of 2017 compared to the Fed’s most recent median forecast of 2.6 per cent. If the market believed the Fed on monetary policy it would expect even lower inflation and a risk of deflation.

Second, the prevailing expectation is of extraordinarily low real interest rates. Real rates have been on a downward trend for nearly 25 years.

The average real rate in the industrialised world over the next 10 years is expected to be zero. Even this presumably reflects some probability that it will be artificially increased by nominal rates at a zero bound and deflation. In the presence of such low real rates there is no sign that economies would overheat.

Many will argue that bond yields are artificially depressed by quantitative easing and so it is wrong to use them to draw inferences about future inflation and real rates. This cannot be ruled out. But it is noteworthy that rates are now lower in the US than their average during the period ofQE and that forecasters have been confidently – but wrongly – expecting them to rise for years.

The strongest explanation for this combination of slow growth, expected low inflation and zero real rates is the secular stagnation hypothesis.

It holds that a combination of high rates of saving, lower investment and increased risk aversion depresses the real interest rates that accompany full employment. The result is that the zero lower bound on nominal rates becomes constraining.

There are four contributing factors that lead to much lower normal real rates. First, increases in inequality – the share of income going to capital and in corporate retained earnings – raise the propensity to save.

Second, an expectation that growth will slow due to smaller labour force growth and slower increases in productivity reduces investment and boosts the incentives to save.

Third, increased friction in financial intermediation caused by more extensive regulation and increased uncertainty discourages investment.

Fourth, reductions in the price of capital goods and in the quantity of physical capital needed to operate a business – think of Facebook having over five times the market value of GM.

Emerging markets hit reverse

Until recently, a major bright spot has been the strength of emerging markets. They have been substantial recipients of capital from developed countries that could not be invested productively at home.

The result has been higher interest rates than they would otherwise obtain, greater export demand for industrial countries’ products and more competitive exchange rates for developed economies.

Gross flows of capital from industrial countries to developing countries rose from $240bn in 2002 to $1.1tn in 2014. Of particular relevance for the discussion of interest rates is that foreign currency borrowing by the private sector of developing countries rose from $1.7tn in 2008 to $4.3tn in 2015.

Developing country net capital flows fell sharply this year – marking the first such decline in almost 30 years, according to the Institute of International Finance, with the amount of private capital leaving developing countries eclipsing $1tn.

Any discussion has to start with China, which poured more concrete between 2010 and 2013 than the US did in the entire 20th century. A reading of the recent history of investment-driven economies – whether in Japan before the oil shock of the 1970s and 1980s or the Asian tigers in the late 1990s – tells us that growth does not fall off gently.

China faces many other challenges, ranging from the most rapid population ageing in the history of the planet to a slowdown in rural to urban migration. It also faces issues of political legitimacy and how to cope with unproductive investment.

Even taking an optimistic view – where China shifts smoothly to a consumption-led growth model led by services – its production mix will be much lighter, so the days when it could sustain commodity markets are over.

The problems are hardly confined to China. Russia is struggling with low oil prices, a breakdown in the rule of law and harsh sanctions. Brazil has been hit by the decline in commodity prices but even more by political dysfunction. India is a rare exception. But from central Europe to Mexico to Turkey to Southeast Asia, the combination of slowdowns in industrialised countries and dysfunctional politics is hurting growth by discouraging capital inflows and encouraging capital outflows.

Assertive stance

What does all this mean for the world’s policymakers gathered in Lima for the IMF and World Bank meetings? This is no time for complacency. The idea that slow growth is only a temporary consequence of the 2008 financial crisis is absurd. The latest data suggest growth is slowing in the US and it is already slow in Europe and Japan. A global economy near stall speed – and slowing – is one where the primary danger is recession.

The most successful recent assertion of growth policy was Mario Draghi’s famous vow that “the European Central Bank will do whatever it takes to preserve the euro”, uttered at a moment when the single currency appeared to be on the brink.

By making an unconditional commitment to providing liquidity and supporting growth, the ECB president prevented an incipient panic and helped lift European growth rates – albeit not by enough.

What is needed now is something equivalent but on a global scale – a signal that the authorities recognise that secular stagnation and its spread to the world is the dominant risk we face. After last Friday’s dismal US jobs report, the Fed must recognise what should already have been clear: that the risks to the US economy are two-sided. Rates should be increased only if there are clear and direct signs of inflation or of financial euphoria breaking out. The Fed must also state its readiness to help prevent global financial fragility from leading to a global recession.

The central banks of Europe and Japan need to be clear that their biggest risk is a further slowdown. They must indicate a willingness to be creative in the use of the tools at their disposal. With bond yields well below 1 per cent it is very doubtful that traditional QE will have much stimulative effect. They must be prepared to consider support for assets that carry risk premiums that can be meaningfully reduced. They could achieve even more by absorbing bonds to finance fiscal expansion.

Long-term low interest rates radically alter how we should think about fiscal policy. Just as homeowners can afford larger mortgages when rates are low, government can also sustain higher deficits. If the Maastricht criteria of a debt-to-GDP ratio of 60 per cent was appropriate when governments faced real borrowing costs of five percentage points, then a far higher figure is surely appropriate today when real borrowing costs are negative.

The case for more expansionary fiscal policy is especially strong when it is spent on investment or maintenance. Wherever countries print their own currency and interest rates are constrained by the zero bound there is a compelling case for fiscal expansion until demand accelerates. While the problem before 2008 was too much lending, many more of today’s problems have to do with too little lending for productive investment.

Inevitably, there will be discussion of the need for structural reform at the Lima meetings – there always is. But to emphasise it now would be to embrace the status quo. The world’s markets are telling us with increasing force that we are in a very different world now.

Traditional approaches of focusing on sound government finance, increased supply potential and the avoidance of inflation court disaster. Moreover, the world’s principal tool for dealing with contraction – monetary policy – is largely played out. It follows that policies aimed at lifting global demand are imperative.

If I am wrong about expansionary fiscal policy, the risks are that inflation will accelerate too rapidly, economies will overheat and too much capital will flow to developing countries. These outcomes seem remote. But even if they materialise, standard approaches can be used to combat them.

If I am right and policy proceeds along the current path, the risk is that the global economy will fall into a trap not unlike the one Japan has been in for 25 years where growth stagnates but little can be done to fix it. It is an irony of today’s secular stagnation that what is conventionally regarded as imprudent offers the only prudent way forward.

The Fed looks set to make a dangerous mistake

August 23rd, 2015

August 23, 2015

Raising rates this year will threaten all of the central bank’s major objectives

Will the Federal Reserve’s September meeting see US interest rates go up for the first time since 2006? Officials have held out the prospect that it might, and have suggested that — barring major unforeseen developments — rates will probably be increased by the end of the year. Conditions could change, and the Fed has been careful to avoid outright commitments. But a reasonable assessment of current conditions suggest that raising rates in the near future would be a serious error that would threaten all three of the Fed’s major objectives — price stability, full employment and financial stability.

Like most major central banks, the Fed has put its price stability objective into practice by adopting a 2 per cent inflation target. The biggest risk is that inflation will be lower than this — a risk that would be exacerbated by tightening policy. More than half the components of the consumer price index have declined in the past six months — the first time this has happened in more than a decade. CPI inflation, which excludes volatile energy and food prices and difficult-to-measure housing, is less than 1 per cent. Market-based measures of expectations suggest that, over the next 10 years, inflation will be well under 2 per cent. If the currencies of China and other emerging markets depreciate further, US inflation will be even more subdued.

Tightening policy will adversely affect employment levels because higher interest rates make holding on to cash more attractive than investing it. Higher interest rates will also increase the value of the dollar, making US producers less competitive and pressuring the economies of our trading partners.

This is especially troubling at a time of rising inequality. Studies of periods of tight labour markets like the late 1990s and 1960s make it clear that the best social programme for disadvantaged workers is an economy where employers are struggling to fill vacancies.

There may have been a financial stability case for raising rates six or nine months ago, as low interest rates were encouraging investors to take more risks and businesses to borrow money and engage in financial engineering. At the time, I believed that the economic costs of a rate increase exceeded the financial stability benefits, but there were grounds for concern. That debate is now moot. With credit becoming more expensive, the outlook for the Chinese economy clouded at best, emerging markets submerging, the US stock market in a correction, widespread concerns about liquidity, and expected volatility having increased at a near-record rate, markets are themselves dampening any euphoria or overconfidence. The Fed does not have to do the job. At this moment of fragility, raising rates risks tipping some part of the financial system into crisis, with unpredictable and dangerous results.

Why, then, do so many believe that a rate increase is necessary? I doubt that, if rates were now 4 per cent, there would be much pressure to raise them. That pressure comes from a sense that the economy has substantially normalised during six years of recovery, and so the extraordinary stimulus of zero interest rates should be withdrawn. There has been much talk of “headwinds” that require low interest rates now but this will abate before long, allowing for normal growth and normal interest rates.

Whatever merit this view had a few years ago, it is much less plausible as we approach the seventh anniversary of the collapse of Lehman Brothers. It is no longer easy to think of economic conditions that can plausibly be seen as temporary headwinds. Fiscal drag is over. Banks are well capitalised. Corporations are flush with cash. Household balance sheets are substantially repaired.

Much more plausible is the view that, for reasons rooted in technological and demographic change and reinforced by greater regulation of the financial sector, the global economy has difficulty generating demand for all that can be produced. This is the “secular stagnation” diagnosis, or the very similar idea that Ben Bernanke, former Fed chairman, has urged of a “savings glut”. Satisfactory growth, if it can be achieved, requires very low interest rates that historically we have only seen during economic crises. This is why long term bond markets are telling us that real interest rates are expected to be close to zero in the industrialised world over the next decade.

New conditions require new policies. There is much that should be done, such as steps to promote public and private investment so as to raise the level of real interest rates consistent with full employment. Unless these new policies are implemented, inflation sharply accelerates, or euphoria in markets breaks out, there is no case for the Fed to adjust policy interest rates.

The writer is the Charles W Eliot university professor at Harvard and a former US Treasury secretary

Comments from ECB Conference

May 22nd, 2015

I commend Mario Draghi and the ECB for their openness in hosting this conference and allowing the presentation of so many perspectives. In the spirit of that openness I shall offer some iconoclastic observations. (more…)

Don’t bet against America.

May 12th, 2015

At the SALT Conference in Las Vegas, NV on Friday, May 8, 2015, Summers told the audience,”This is not a society that is stuck. It is a society that is uniquely able to be resilient through a constant process of savage self-criticism.” (more…)

Concern growth is not going to pick up

May 7th, 2015

On Thursday, May 7, 2015, Summers talked with Bloomberg’s Stephanie Ruhl and Erik Schatzker at the Salt Conference in Las Vegas, NV. They discussed Treasury yields, Europe, China and concerns about growth in the United States. Summers talked of the “dawning and growing awareness in the market of the idea we may have a chronic excess of savings over investment in the economy — a phenomenon known as secular stagnation.” (more…)

Larry Summers: Raise the minimum wage

April 28th, 2015

A ‘maddening’ situation: Larry Summers, the former U.S. Treasury Secretary under President Bill Clinton, had a similar take.

He warned that America’s economy is entering a period of stagnation — he dubs it “secular stagnation” — where it won’t be able to achieve its full growth potential because everyone is saving too much and not spending.

“We are doing less investment in infrastructure than at any time since the Second World War on a net basis,” Summers told Zakaria.

He went as far as calling the situation “madness” since it’s incredibly cheap to borrow money right now when interest rates are at a record low.

“[This] is a moment for us, as a country, to do what a business would do, which is to take advantage of low borrowing costs to invest in our future,” said Summers, who worked as a top adviser to President Obama. “This is not the right moment for a lurch to austerity.”

The U.S. economy grew 2.4% last year. That’s good, but not great. Since the end of World War II, America’s economy has expanded over 3% a year, on average. It has yet to get back to that point after the financial crisis.

Not the Right Moment for Lurch to Austerity

April 21st, 2015

In an interview on April 19. 2015, with CNN’s Fareed Zakaria, Summers said, “This is a moment for us, as a country, to do what a business would do, which is to take advantage of low borrowing costs to invest in our future.” Summers told Zakaria, “This is not the right moment for a lurch to austerity.” (more…)

Thought Economics: Modern Capitalism

March 20th, 2015

In an exclusive interview with Prof. Summers and Prof. Edmund Phelps, Thought Economics looks at the story of modern capitalism, the benefits it has brought, and the challenges it has created. The series explores the ‘post crisis’ economy, the role of government in society, the relationship between capitalism, conflict and inequality and looks at what needs to be done to ‘fix’ our global economy, and the science of economics itself. (more…)