While I do not believe the Fed made a serious mistake Wednesday in raising rates, I believe that the “preemption of inflation based on the Phillips curve” paradigm within which it is operating is highly problematic. Much better would be a “shoot only when you see the whites of the eyes of inflation” paradigm of the kind I have advocated for the past several years.

Such a paradigm would be more credible, more likely to result in the Fed’s satisfying its dual mandate, reduce risks of recession, and increase the economy’s resilience when recession comes.

Many of my friends have recently issued a statement asserting that the Fed should change its inflation target. I suspect, for reasons I will write about in the next few days, that moving away from inflation targeting to something like nominal gross domestic product-level targeting would be a better idea. But I think that this issue is logically subsequent to the question of how policy should be made in the near term with the given 2 percent inflation target.

Five points frame my doubts about the current approach.

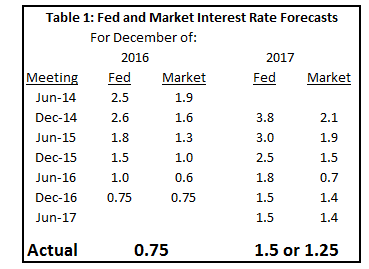

First, the Fed is not credible with the markets at this point. Its dots plots predict four rate increases over the next 18 months compared with the markets’ expectation of less than two. Table 1 shows the Fed has been highly unrealistic in its forecasts for several years.

There are some caveats in comparing market and Fed forecasts. Yellen is not necessarily the median dot but has disproportionate influence. Additionally, the dots refer to the modal (most likely) rather than the average future scenario. Both those factors might tend to make the Fed forecast overstated, if Yellen is more dovish than the Fed as a whole. But on the other hand, market forecasts contain term premiums that are on average positive, implying that market expectations for Fed policy should also be biased to the upside. In sum, there is no rationalizing away the protracted pattern of Fed forecasting errors except to doubt the models on which the Fed is relying.

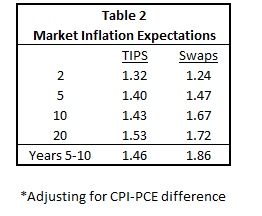

The truth is that markets do not share the Fed’s view that inflation acceleration is a major risk. Indeed they do not believe the Fed will attain its 2 percent inflation target for a long time to come. Table 2 shows that neither inflation indexed bonds nor the swap market expect the Fed to hit its 2 percent PCE inflation goal in the foreseeable future.

If the Fed were equally behind the curve with respect to rising inflation there would be hysteria among the commentariat. They would be proclaiming that the Fed has to move decisively so as not to be behind the curve. Why shouldn’t there be concern about disbelieved forecasts of actions that if taken would push inflation further below target than current forecasts?

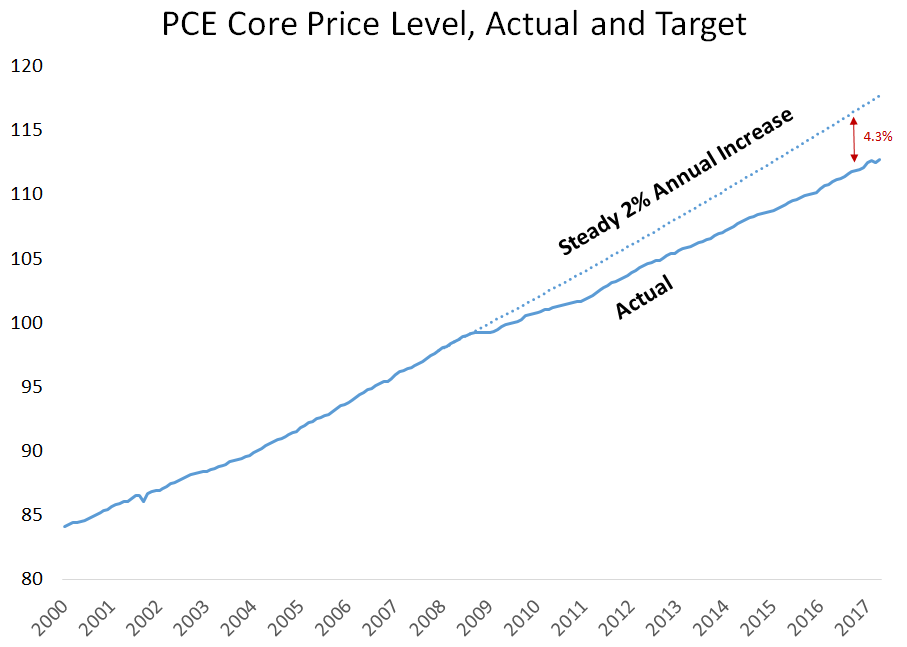

Second, the Fed regularly proclaims that it has a symmetric commitment to its 2 percent inflation target. Recoveries do not last forever, and when recession comes, inflation declines. So why would the Fed want to be projecting only 2 percent inflation entering the 11th year of recovery with an unemployment rate clearly below their estimate of the NAIRU, or the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment? Such a prediction is coming after a full decade of sub-target inflation. As shown in the graph below, the PCE core price level is a full 4.3 percent below where it would be had it risen by the Fed’s target amount over the past decade.

Accordingly, policy should be set with a view to modestly raise target inflation, perhaps to 2.3 or even 2.5 percent inflation, during a boom with the expectation that inflation will decline during the next recession. A higher inflation target would entail easier policy than is now envisioned.

Third, preemptive attacks on inflation, such as preemptive attacks on countries, depend on the ability to judge threats accurately. The truth is we have little ability to judge when inflation will accelerate in a major way. The Phillips curve is at most barely present in data for the past 25 years. And as Staiger, Stock and Watson demonstrated years ago, the NAIRU, assuming such a thing exists, can only be estimated with extreme imprecision.

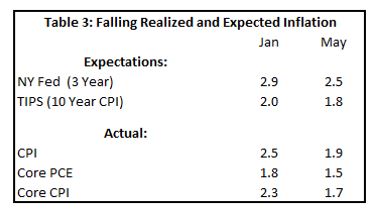

At some points these might seem like theoretical arguments. But in recent months both overall and core inflation have come down along with market and survey measures of inflation expectations. The most widely followed inflation measure, the consumer price index, has decelerated from 2.5 percent inflation in January to 1.9 percent. Accordingly, inflation expectations have fallen 0.2-0.3 percent. This behavior is contrary to all the Fed staff models.

With inflation and inflation expectations below target and declining, there would be little case for preemption even if inflation above target was a serious problem. But as we have seen, there are strong reasons for thinking that the Fed should, to be consistent with its mandate, let inflation rise above 2 percent.

Fourth, as I have stressed in my writings on secular stagnation and in a recent conversation with David Wessel, there is good reason to believe that a given level of rates is much less expansionary than it used to be given the structural forces operating to raise saving propensities and reduce investment propensities.

I am not sure that a 2 percent funds rate is especially expansionary in the current environment. And I am confident that if the Fed errs and tips the economy into recession, the consequences will be very serious given that the zero (or perhaps slightly negative) lower bound on interest rates will not allow the normal countercyclical response. This too counsels a bias toward expansion.

Fifth, a “whites of their eyes” paradigm does not require the Fed to abandon its connection to price stability. It simply needs to assert that its objective is to assure that inflation averages 2 percent over long periods of time. Then it needs to acknowledge that although inflation is persistent, it is very difficult to forecast and signal that it will focus on inflation and inflation expectations data rather than measures of output and employment in forecasting inflation.

With these principles internalized, the Fed would lower its interest-rate forecasts to those of the market and be more credible. It would allow inflation to get closer to target and give employment and output more room to run.